How to Build a High-performing Team under Pressure Within an OEM or "One SOP per Day" (Part 1 of 2)

2018 has probably been one of the most exiting years in my life. My team and I became a high-performing team by finding our vision, our mission and our organization structure, which allowed us to link the corporate world to the agile world. We aimed for one code release per day (called SOP or start of production in Automotive language), which meant we were working under a lot of pressure. But I believe that without the pressure motivating us, we wouldn’t have achieved our goal. So embrace the pressure and read on if you are curious about our journey. This is part 1 of a two part blog post.

The introduction: Lessons learned in the past

After earning my PhD in predictive analytics 8 years ago, I joined Volkswagen as a candidate for their planned job rotation in 2010. This pilot program was designed to have me spend three years in the research department before rotating to the IT group. The first three years were designed to acquire foundation knowledge about the company to then go on to build the group-wide, automotive, backend system in my IT-years afterwards. And when the day came for my rotation, I was ready and willing to play a leading role in ensuring that Volkswagen would deliver the best and most-innovative digital online services the company had ever experienced.

When I came in, the IT group was made up of a handful of highly skilled experts, trying to transform Volkswagen’s IT function from facilitating the manufacture of the best cars in the world to implementing the best mobile online services in the world. We felt like Marvel super heroes during those crazy times. Within the first weeks, I took on the role of IT Architect for the Chinese market. China had a large volume of cars and was the most innovative market regarding mobile online services. Although I was initially overwhelmed, I knew this was a great opportunity and I was grateful for the chance to prove myself. I strategically planned and prioritized all tasks until I was ready to conquer my target market. I aimed to achieve my first three action points within the first three months. I hired freelancers for all necessary tasks and was drowned in meetings and emails for 6 months! I was really stressed.

At this point, I sat down and reviewed my action plan. I couldn’t believe what had happened. Could it be true? In twice the allotted time, I was only able to complete one of my 3 action points even though I had 20 freelancers on my payroll! How could this happen? I talked with a trusted colleague who told me the following joke:

- How was God able to create the universe in only six days?

- Answer: He didn't have any legacy systems.

We laughed together and then I realized that the legacy systems were our bottleneck. How could it be that I had 20 freelancers on my payroll but the output decreased proportionally by the number of people I employed? Simply put, I got more money for solving the problems but by employing more freelancers, I burned more money and achieved less. It was a sinking feeling and I knew I had to make a change before bubble hit bottom and exploded. My colleague then told me this riddle:

- How many people do you need to dig a hole in one day?

- One, I answered.

- He continued, Now I give you hundred. How many days will you need now?

I looked straight into his eyes and answered totally confused: “One.”.

One week later we had scalability issues on the production system in Europe. It was recommended that I fix the problem since some of the services would soon be migrated to the Chinese market. If my team and I were not able to fix these issues here, I would have bigger problems in China, where the traffic was much higher. So I was very motivated to solve this problem. One colleague suggested that the storage area network (SAN) was misconfigured on production. If that was the case, the solution would show itself if we reproduced the problem on the staging system and analyzed how the configuration could be optimized. Imagine my shock when I learned that the staging system was not identical to the production system. I couldn’t believe it. If only I really had a superhero’s cape in the closet! Only a superhero could solve such a production problem without downtime. I wasn’t sure we were up to the task. Could it be that I was surrounded by really smart people but together we did not make a high performing team? Did we have a real chance to become one?

Lessons learned:

- Legacy is always the bottleneck in big companies.

- External developers won’t be effective if legacy systems are involved. You cannot solve all problems by simply increasing the manpower.

- An identical staging environment is essential to timely problem solving.

Two years later in 2016, I found myself in Berlin Kreuzberg. I wore skinny jeans, had a Macbook full of cool stickers, spoke at cool conferences and worked with a great team of developers, two of which held PhDs in Physics. During lunch they talked and told jokes like the cast of Big Bang Theory. It was fun. I was happy.

Looking back it all began when I met Roland over a beer at a conference in Nuernberg. I gave a lecture there on how to make websites smart. I described how I added machine learning to my hobby website, foodplaner.de to analyze the users’ food intake, and how I generated perfect-matching meal plans out of billions of possible configurations. Roland explained to me how the agency he worked for earned their money by offering a proxy server. Their clients fed their website into their proxy server and received an optimized responsive website which was faster than before. I was truly impressed. Soon we started to brainstorm: how to offer additional services. We came to the conclusion that it would be really cool to have some kind of analytics to ensure that their customers had the best performance on their website. One and a half years later we had a cool dashboard, a scalable architecture based on the Amazon cloud and a cool algorithm that we had presented at a top conference in the world (the WWW conference Developers Day 2016) where we met Tim Berners Lee and Peter Norvig. It felt like we really were a high-performing team.

How could it be that I was able to achieve this in 1,5 years with 5 people but I wasn’t able to complete more than 1 task at Volkswagen in 6 months? How could we be so fast and innovative? Why were we so high-performing?

Lessons learned:

- We used state-of-the art technology (cloud and open-source)

- We had no legacy systems

- We were a small but cross-functional team of in-house developers

June 2018: The Phoenix Project

I was on my way back from an icebreaker session at a conference in Berlin. While there, I gave a talk about scalable DevOps solutions in big companies and promoted our open job positions. Afterward, I drank some beers with some participants of the session and then shared a walk with a colleague from Scania. I told him that I’d previously worked in Berlin for an agency, where, with a great team, we accomplished a lot in a short time period. Then I confided in him about the past six month and the current team I was working with at Volkswagen Commercial Vehicles and how unproductive we were despite all our experience and expertise. I was afraid we’d miss our deadlines. I didn’t understand it. I was under a lot of pressure. What if we miss the start of the production deadline and Volkswagen started burning thousands of euros every day as a result? I would definitely loose my job. How could it be that a corporate environment is so different from a startup environment?

He patiently listened and then recommended that I read the book, “The Phoenix Project”. Reading it has been a great experience for him and it had helped him understand the most common mistakes made within corporate environments in terms of IT projects. Most importantly, the book explained if you didn’t avoid making these mistakes, it would be impossible to become a high-performing team.

It was a fast read. I read the book over one weekend and was amazed that the author touched on all the faults that we had made as a team. How could it be that he wrote this book in 2014? Did he have a time machine? Then it became crystal clear to me. He simply described all the standard mistakes that all companies make when they start digitizing their value chain. By the end of the book, I believed that we had a chance to become a high-performing team. Now, I knew which errors I had made when working for the group IT at Volkswagen and which ones I had avoided while in Berlin with the startup, since it was a totally different setting. But my main take-away from the book was:

If you don’t aim for building cross-functional DevOps teams and go for automated testing and continuous integration, you’ll never be able to achieve great performance as IT team. You have to aim for at least 1 deployment per day.

On Monday, I presented the book to my team and suggested they each read it. In the meantime, I researched best practices for building high-performing teams. Since I hadn’t found the Phoenix Project on my own, I wondered what else I had missed in terms of related work.

Related work for building high-performing teams: Clarity and psychological safety

I started by searching what were the key factors to become a high-performing team (aside from building the right IT environment, which I had learned from the Phoenix project). I found a study from Google, where they analyzed the most important aspects of high-performing teams, which was psychological safety. Next search: “What is psychological safety?” It’s the importance of feeling safe to share ideas without harsh judgement or ridicule. Like when you’re in a meeting with your team, and you have a really wild, out-of-the-box idea, and you are comfortable enough to share it without expecting comments like, “You’re a total idiot,” or “That’s a terrible idea. Why did you say that?” This notion of feeling safe (aka supported) in meetings is very important. Google has a range of ideas for how you can implement and develop psychological safety within your team. If you’re the manager, for example, and you’re in the meeting where you notice that someone is dominating the meeting, you can step in and ask someone who’s not spoken yet to speak up. There are many more similar tips on their website.

But here is where things get tricky. In my experience, all the teams that I have worked with, ever since I started at Volkswagen, have been very diverse teams. At Volkswagen, we believe that diverse teams have better outcomes. For example, people of different genders, different backgrounds and those with or without PhDs. The notion of psychological safety, however, is based on trust. And there is well-documented research that we usually trust people who look similar to ourselves, or who have similar experiences as ourselves. When I’m in a large group of predominantly business people and I see another person wearing a nerdy IT shirt, I naturally prefer to talk to this person since it is more likely that I have something in common with him/her. So how am I going to build psychological safety and trust in a team that is very diverse? It came down to this final question for me: How can I create an environment that fosters psychological safety and diversity?

Before I foster psychological safety, I need to address conflicts within teams. People often think that psychological safety means harmony. But harmony is not what you need, does not foster new, out-of-the-box ideas and is not very creative. Instead, what you want to foster is constructive conflict. This means that team members are able to challenge each other’s ideas in an environment where no one feels threatened by the challenge. But here is the dilemma. In a very diverse team, where people are bringing different perspectives to the table, insidious conflict starts when different people are solving different problems that they think are the same problem. This is not very constructive, which breaks down the psychological safety. This is the reason why teams have to define a crystal-clear vision and mission.

To elaborate, if you say, “We need to build the best fleet management system in the world,” your team will interpret that statement in different ways based on their background, their education and what companies they worked at in the past. They will each have a different interpretation of what is best, how fleets should be managed and how big the world is. They may start building totally different things while working together on the same project. This is why clarity is so important. And clarity means it has to be crystal-clear. One of the most important things that I learned, not only at Volkswagen, but also at other companies, is the higher up that I went, the more important clarity became. For every line of code, everything that you do, you should empower your teams to get as much clarity as possible to fully understand the problem. The best outcome is that you will have people on your team with different backgrounds, skill-sets and approaches to solving the same problem.

Additionally, a big part of clarity is defined, not only on what you’re doing, but what you’re not doing. And focusing on what you don’t do is as important as knowing what you do. It’s also important to be customer-centric since this helps define clarity enormously. As an IT department, we have a lot of different internal customers: product management, the sales department and people at other brands of the Volkswagen group. So understanding who you’re building the product for can be really clarifying. Who is the customer, who is a stakeholder and who is your investor?

In the beginning, we mixed this up and thought our investor was our customer. Finally, we understood that we have to set the driver first. When the driver is happy and uses our product with joy, the fleet manager is happy, since he gets data. Then our system is frequently used and the other brands bring it to their cars as well.

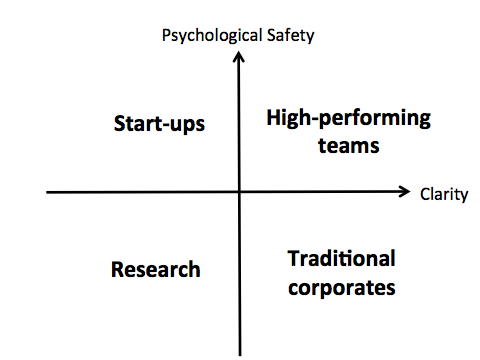

We’ve talked about psychological safety, about clarity and how you want different approaches to the same problem. This is how I’ve visualized the outcome of both metrics:

On one axis is psychological safety and on the other clarity. We’ll walk through each one of these quadrants.

Quadrant 1 (upper left): This scenario can be found in the start-up scene. People who have previously worked together in a start-up often work together afterwards on the next project. In Berlin there is the so-called Rocket-Mafia, where founders are funded by the venture capital firm Rocket Internet and during this time they build such a strong bond that they found upcoming start-ups together, too. Nevertheless, many times they don’t know as a group, where their journey will end. Maybe they’ll build a unicorn or a flop and start over with the next try.

Quadrant 2 (lower left): If you neither have psychological safety nor clarity, then you have total, complete chaos. I’ve found this setting in research environments, e.g. during my PhD. time. PhD students often work on their own and try to protect and fight for their idea. There is also a high fluctuation at research departments at universities due to the restricted time of a PhD. People come and go. If people don’t know each other very well, they don’t trust each other and they don’t know what they’re working on. This is a very challenging environment to work in.

Quadrant 3 (lower right): The same holds true for the traditional corporate quadrant. A strong hierarchy often occurs in big companies where you’re told very specifically, all the time, “You need to ship this, you need to ship that,” but the wrong values are in place. If a company is still committed to their old values like control and micro-management, the clarity may be good but people don’t feel psychologically safe. They don’t trust to push back. They don’t trust to challenge ideas because they are afraid of being politically or emotionally “shot down.” There are so many ways to bully people in big corporations. This is what may be found in traditional companies.

Quadrant 4 (upper right): Now let’s look at the high-performing teams quadrant. I think this is the quadrant where my team and I accidentally stumbled into. The reason is that we had absolute clarity (a very clear deadline, the so-called start of production of the car). It was crystal clear what the goal was: We had to aggressively cut scope. We had to approach this really intensely. But we had extreme clarity. We also had really great managers in the other departments we worked with who trusted us and fostered psychological safety. So the short answer of why we were successful, we’ll never really know, but psychological safety and clarity were very much present. Now what does that mean for my team developing a fleet management solution? To be able to finally end up as such a team, we needed a framework for building clarity and psychological safety in a structured way and to be able to pave the way for continuous improvement.

Conclusion

Part 1 explained how we found at which are the important aspects to become a high-performing IT team within an OEM: Psychological safety and clarity. Be aware of all common mistakes you may make. Read the book "The Phoenix Project" from Gene Kim and think about your value chain. Part 2 will explain which framework we used to systematically build up clarity (finding our vision and mission) and psychological safety (by defining our organization structure and values) as a team. Stay tuned!